All products that are certified as being environmentally or socially responsible have to rely on a Chain of Custody system to keep track of products as they move along the supply chain. And all such systems are potentially open to fraud. Can blockchain, the much-talked about code behind Bitcoin, help keep these systems secure?

Read this article to find out:

- The potential for fraud in paper-based Chain of Custody systems.

- A not-too-technical explanation of what blockchain is.

- An explanation of how blockchain might be able to create Chain of Custody systems that are (virtually) fraud-proof.

The potential for fraud in paper-based Chain of Custody systems

All environmental and social certification systems need a way to track products that meet the scheme’s requirements from forest or farm or sea through the supply chain all the way to the final consumer. Supply chains can be long and complex, with a risk that companies can cheat the system, either on purpose or by mistake, by diluting the certified material with non-certified.

At the moment, many certification schemes rely on paper-based Chain of Custody (CoC) systems. That means that every company throughout the supply chain has to keep paper records of the quantity of certified products that they buy and sell. It also means that auditors have to come in to check those paper records.

The problems with this system are that:

- It is open to fraud. Many of the current Chain of Custody systems lack an efficient method to control volumes through the supply chain, and this weakness can be abused by the less scrupulous. As a certifier, we have come across several cases where organisations have cheated in this way. For example, we have been working with FSCTM on uncovering volume fraud in charcoal supply chains.

- It is expensive. A paper-based CoC system requires all companies along the entire supply chain to be audited on a regular basis.

Blockchain technology holds out the promise of being able to overcome these issues.

What is blockchain?

Blockchain is probably best known from bitcoins – the internet money. Blockchain is a ‘decentralised ledger’ technology that keeps records of chains of data.

- The ‘decentralised’ bit means that multiple copies of the data are distributed across a network of computers – so there are lots of identical copies in existence.

- The ‘ledger’ bit is just a fancy way of saying a chain of information, such as financial transactions or purchases and sales in a Chain of Custody.

A clever bit of cryptology ensures that only one piece of new data can be appended to the end of the chain and that only one version of the chain is valid. The system manages to do this by having the information distributed on multiple computers, and by requiring all computers to agree on the valid version of the data. This means that copies that conflict with the consensus, i.e. that have been tampered with, are rejected.

In theory, the volume of certified product could be inflated, but only if there was collusion between all the different people running all the different versions of the database. In practice, as long as the database is distributed among enough different people, this would be very difficult to do.

The potential for the blockchain to create tamper-proof Chain of Custody systems

A Chain of Custody system running on the blockchain offers the advantages that:

- It is (virtually) tamper-proof, overcoming the issues of potential volume inflations of a paper-based system.

- It is cheaper than a paper-based CoC system. If you’re a trader that does not take physical possession of the products, then a blockchain-based CoC system would probably require very little auditing and therefore considerable cost savings. If you’re a manufacturer, then a blockchain-based CoC system could mean fewer audits as there would be less need for paper checks and because the auditing that does take place could be done on a risk-based approach.

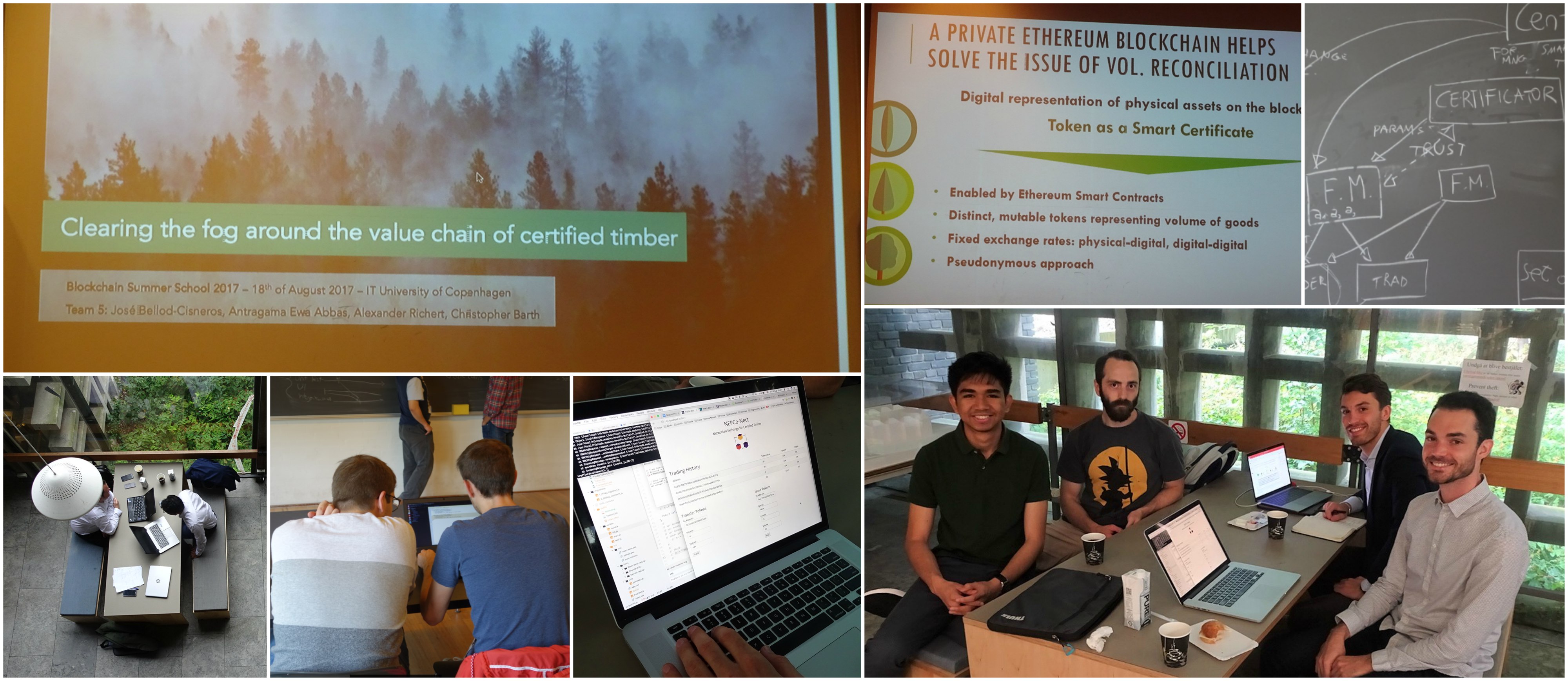

To explore whether this sort of authenticated distributed ledger technology could be useful for CoC systems, we took part in a Blockchain Summer School at the University of Copenhagen. The event was an initiative of the European Blockchain Center. We presented a use-case for adapting the blockchain technology to track FSC-certified timber along supply chains. Two groups of computer science students worked with us to come up with a prototype. They had 72 hours (3 days) to work on this in a so-called ‘hackathon’.

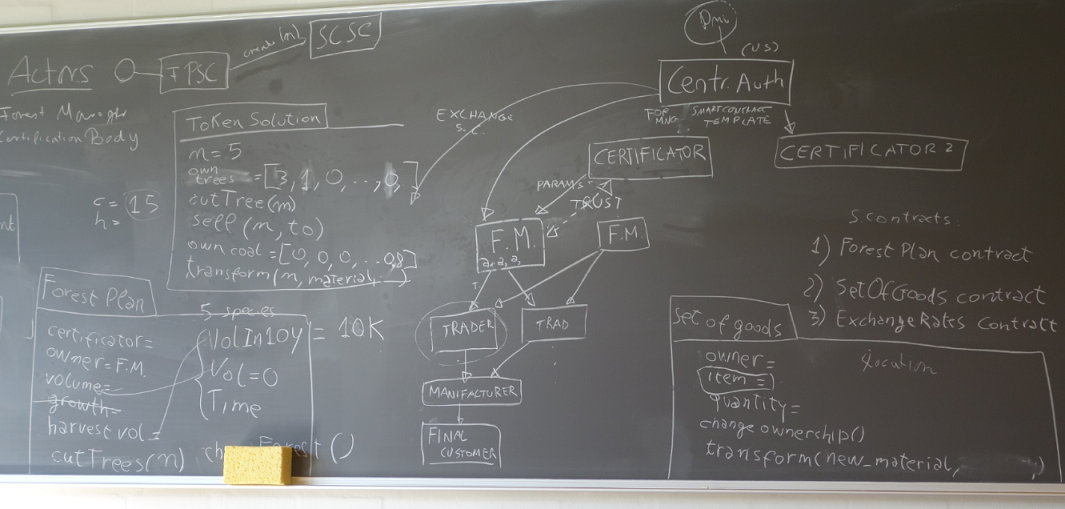

The prototype worked like this:

- The volume of wood was recorded in the form of ‘tokens’. The tokens had attributes such as species, origin, certification claim and type of product.

- People buying and selling certified wood had an online ‘wallet’ containing their tokens.

- The blockchain kept a record of the journey of the tokens along the supply chain.

- Forest managers had the right to create new tokens based on their expected harvesting volumes. In practice, the creation of new tokens would be controlled by a certification body.

- To complete a transaction, the seller had to not only issue a regular sales invoice, but also send a digital token to the buyer.

- One cubic metre of roundwood does not make one cubic metre of sawnwood; wood is lost as sawdust and waste along the way. Because of this, the prototype built in a conversion factor. We assumed that 1 token of pine roundwood would be converted to 0.5 tokens of pine sawnwood. In practice, the system could be set up to use conversion factors that are verified by auditors. One possibility would be to require companies that use a better-than-average conversion factor to seek approval from the scheme owner or certifier. For example, in palm oil certification by RSPO, standard conversion factors are given and any deviations must go through a special approval process. Wood is a more complicated material than palm oil, but the principle is the same.

The team developing the blockchain protocol came up with the following slogan to describe the process: “No tokens in the wallet, no tokens for transactions, no certified sales”.

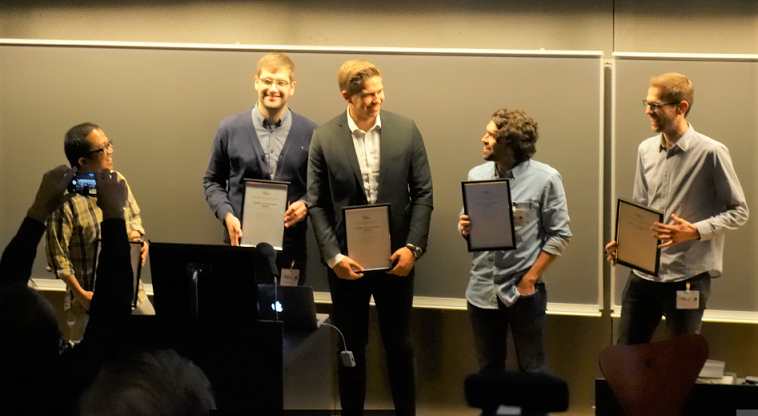

The summer school had other use-cases from fintech to solar energy, and after burning the midnight oil for three nights in a row the students working on the timber-tracking solution won the prize for the best solution produced in the start-up category. We were happy to use the opportunity to explore the blockchain as a way to track certified volumes of timber and we’d like to thank all the students for their enthusiasm and hard-work – we learnt a lot!

Of course, there will be challenges to using blockchain in CoC systems as well. Some of those are technical issues. For example, for tracking certified timber, a system would need to be able to take into account:

- Assembled and multi-material products. A timber CoC system is not as simple as tracking a certain volume of one species of timber through the supply chain, as it will need to be able to deal with products that are assembled from lots of different materials. One solution to this could be to use a combination of different types of token in one product.

- Sales of certified material as non-certified products. For example, a seller may only want to sell a product as being certified if the buyer is willing to pay a premium; if the premium isn’t paid, then the product is sold as uncertified. One solution to this could be to enable tokens to be removed from the online wallet.

Despite these challenges, our feeling is that blockchain holds the potential for transforming the Chain of Custody systems for all certified products in the near-future, making them both more trustworthy and cheaper for companies to implement.